News

News

NCSC Boss Talks On China, Russia and Trust In Tech

A few days after the coronavirus lockdown began, Ciaran Martin’s phone pinged with a text message – the government was warning him he had left home three times and had to pay a fine.

As the official in charge of defending the UK against cyber-threats, he knew enough to spot a scam.

But it was also a sign he was unlikely to have a quiet end to his time as the first head of the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC).

Speaking in his last few days in office, he says recent events have been an “unexpected vindication” of the decision to spin out part of the intelligence agency GCHQ so classified intelligence could be better shared to protect the UK.

Pandemic Protection

Cyber-criminals were quick to exploit Covid-19, using it to persuade people to click on links or buy fake goods.

And that placed new demand on systems built to automate cyber-defences and spot spoof messages.

At the same time, the NCSC had to help government and public-sector organisations deal with the sudden increased dependence on technology, whether in the cabinet meeting over video link or the government sending out genuine text messages to the entire public.

But it was not just cyber-crime groups who were on the move.

Foreign spies also began to go after new targets.

And protecting universities and researchers seeking a coronavirus vaccine became an urgent new priority.

“Many of the people involved never thought they’d be in a case where they’d be talking to part of an intelligence service about resisting major nation state threats against their work,” Mr Martin says.

In July, the UK, along with the US and Canada, accused Russian intelligence of trying to steal research.

The accusation – known as an “attribution” – came because the NCSC could draw on GCHQ’s long history monitoring Russian hackers.

“We have built up significant knowledge of some of the major attack groups from the major nation states, including Russia, over more than two decades,” Mr Martin says.

“For a lot of the things that we were seeing in the high end of vaccine protection, it was detected by us because it was the more sophisticated end, where the attacker is trying harder not to get caught.”

‘Protect The NHS’

The health service in general needed extra protection to avoid any possible disruption to its work.

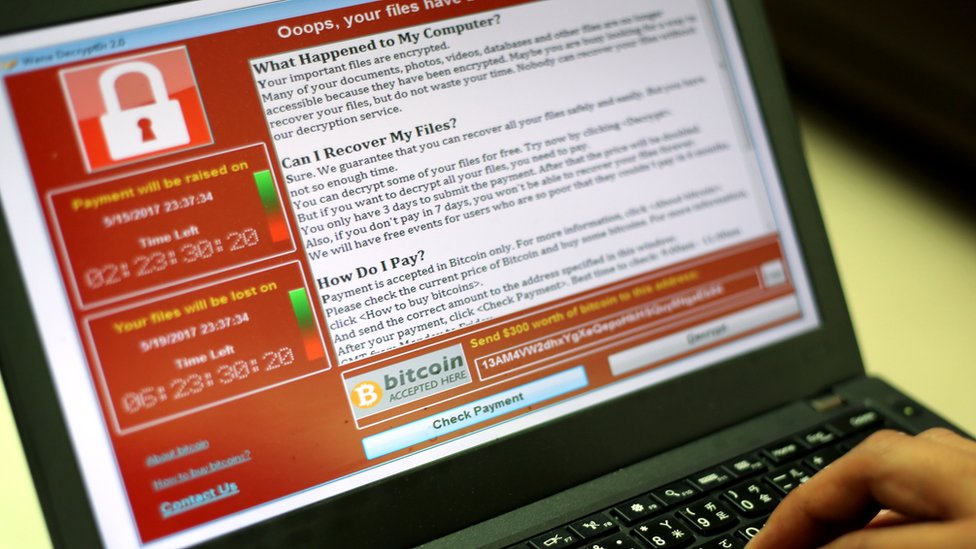

It had already been the victim of the biggest crisis on Mr Martin’s watch, during the WannaCry attack, in 2017, when ransomware locked many NHS trusts out of computers.

That, he says, came close to being labelled the first ever “category one” cyber-event – meaning it was a national emergency.

And it avoided the label only because most of the crippled systems were non-critical, such as appointment bookings.

Major Risk

The WannaCry attack did not even deliberately target the NHS.

Instead, it originated in North Korea and escaped into the wild.

And Mr Martin says this remains a major risk.

“My guess would be the next cyber-crisis will probably be, at least in part, an unintentional consequence of an attacker not really understanding what they’re doing,” he says.

His worry is someone working in a company or government department makes a small mistake – leaving an important system open to ransomware.

‘Rueful’ Joke

Mr Martin’s time at NCSC has seen cyber-security move from a side-bar to the centre of political debate, intertwining with geopolitics and wider national security issues.

The “rueful” joke among colleagues, he says, is it was much easier when no-one cared.

This year, the NCSC was central in the government reversing course over Chinese company Huawei’s role in 5G telecoms, after US sanctions necessitated a technical reassessment.

“We have never been in any way naive about risks associated with Chinese technology,” Mr Martin says, arguing the UK needs to think hard about where it positions itself as cyber-space increasingly fractures.

And this includes doing more to protect its own technology industry, especially in strategically important areas such as quantum computing.

“The UK has got some brilliant technology,” he says, “and sometimes we let it leave the country too easily.”

Constant Concern

Mr Martin says the NCSC has not seen the need to issue specific guidance about Chinese company TikTok, however, which the Trump administration claims is a threat to US national security.

“The amount of personal data it collects, people need to be aware of,” he says, but “it is slightly less than some of the others”.

And while China has risen up the agenda, Russia has been the more constant concern for the NCSC.

“It was high tempo – it was relentless – it did evolve. So we are talking a lot more about political interference in 2020 than we were in 2014,” Mr Martin says.

Russia was accused of interfering in the 2019 general election by hacking and leaking trade documents.

“It shows that there is an ongoing threat to democratic processes,” according to Mr Martin.

But he says: “It is not the case in my judgement that there has been sustained high-quality effective disruption of UK politics by the Russians.”

Spy Agencies

Mr Martin defends the intelligence services against the accusation in the recent “Russia report” they have not focused enough on the threat from Moscow.

But he also says it should not be the job of spy agencies to regulate political debate.

“No-one wants to live in a country where the likes of parts of GCHQ or MI5 are in charge of verifying political information in the midst of an election,” he says.

And as he leaves the civil service after 23 years, for a position at Oxford University, he remains a cautious optimist about technology.

The priority, he says, will be making the internet easier to use safely, particularly as our dependence on technology continues to accelerate

Recent Posts

- Pakistan Opens Doors to Boost Tourism and Business with Free Visas for 126 Countries

- Disney’s “Inside Out 2” Becomes the Highest-Grossing Animated Film Ever

- South Korea Cracks Down on Crypto Exchange Fees

- Ava Kris Tyson Departs MrBeast Following Grooming Allegations

- Apple’s iPhone SE 4: What do we know so far?

- ‘Inside Out 2’ Crushes Box Office and Enters the Billion-Dollar Club

- Telegram Founder Backs Viral Crypto Game Hamster Kombat, Calls it a New Era for Blockchain

- End of the Road for Self-Lacing Nikes: App Shutdown Leaves Adapt BB Owners with Limited Functionality

- Chaotic Encounter During European Tour Leaves IShowSpeed Injured and Frightened

- Quirky RPG ‘Thirsty Suitors’ Coming Soon to Mobile on Netflix Games